Eddie Harris and Me…

I like to hear anybody that is individualistic, especially if they are individualistically minded. You can hear it come out in their playing... Monk, Miles, Duke, Sun Ra, Kool and the Gang, Sly (Stone), Bartok, Schoenberg...anything that people do that is unique and different.

Eddie Harris

I practice eight hours a day. How do you think I can play all the things I play? I play at fast speeds for all the things I do on the saxophone, you've got to put time in. I make no bones about it. You talk with (guitarist) John Scofield and all these cats, they'll say, "Hey man, if we're in a hotel with Harris, put him in 101 and us in 1120. We'll never get any rest."Eddie Harris and his multi-instrumentalist discipline

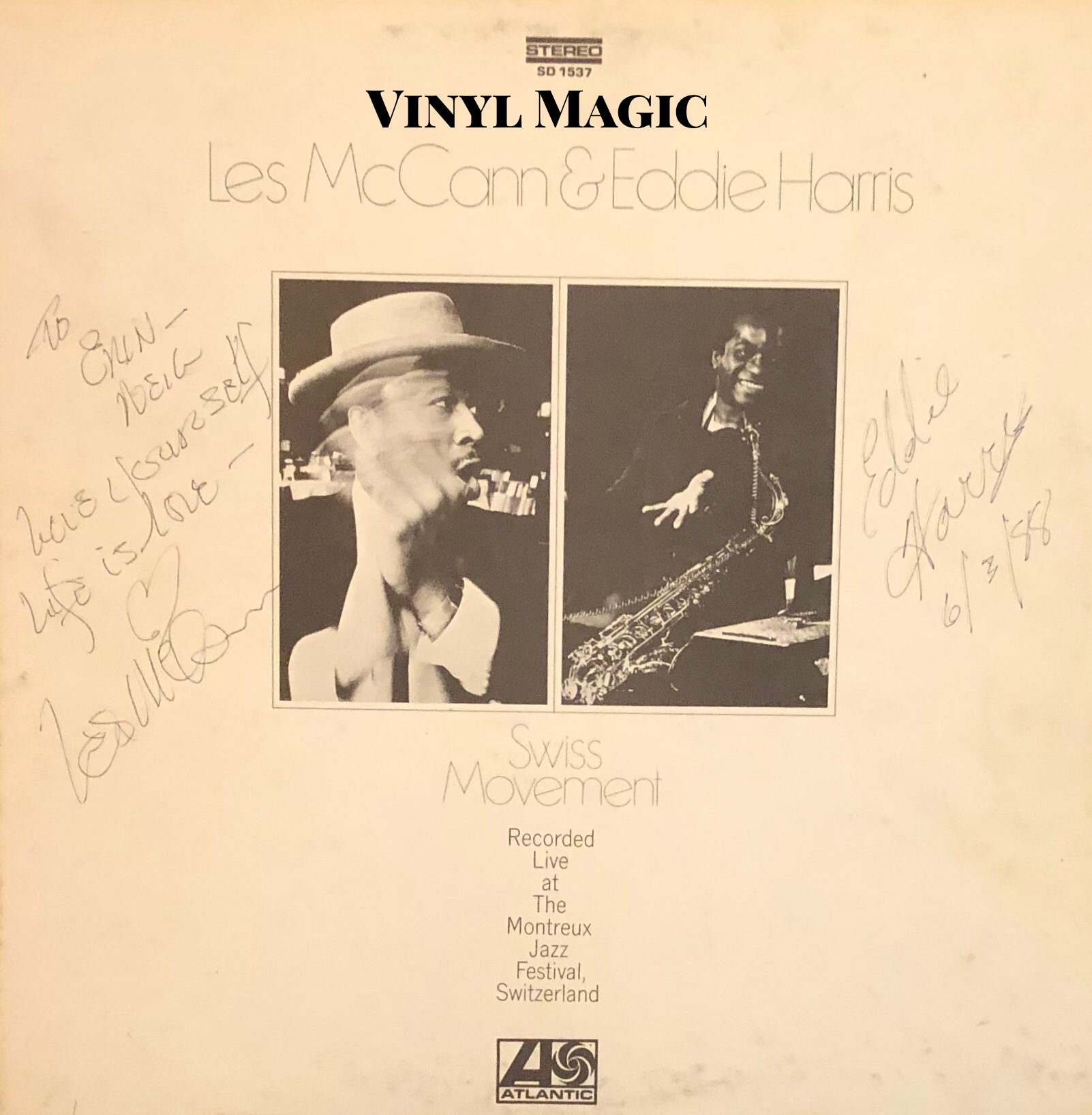

Swiss Movement (1969) signed by Eddie, Les McCann

Billie Holiday was very instrumental in trying to get me to understand that I could not only swing, that I played melodically. I was playing at the Pershing Lounge opposite Ahmad Jamal, and played off nights. She had a club underneath, which at first she called Birdland, then the people in New York wouldn't allow her to call it Birdland, so she changed it to Budland. She came down one time, when we were rehearsing during the afternoon... She came down to these rehearsals, any time she could, and she directed the rehearsals, "Hey, don't do that!" ...and she said, "You can really phrase, your timing..." and she used a lot of four-letter words...

Eddie Harris on his piano skills and his sharpest critic

It’s strange. People like my piano playing. I wish they would like my saxophone playing like that. I don’t know what it is. The piano playing, maybe it’s because I can groove, I get across to the average John and Jane Doe. The saxophone, I don’t know what it is, I’ve never had that happen.

Eddie Harris

I've been open minded. I listen to people, like what I like, dislike what I dislike, just the same as everyone else. I believe if you're playing a salsa tune, you try to improvise on the way the melody was constructed. If you're playing a tune where you want to take extreme liberties, in what you call avant garde jazz, you try to solo accordingly. That's all I've tried to do all my life in playing music. Therefore, people haven't always known how to program me. They'll say, "Oh, he's the cool cat because he did "Exodus." Then, "Hey man, what's this "Freedom Jazz Dance?" What is that?" Then, "What's he doing, man, playing with his echo on his horn or playing a tenor with a trombone mouthpiece? He shouldn't do that."

Eddie Harris

The Soul Of Eddie Harris (1961 recordings, 1968 release) unsigned

Arranger, author, composer, inventor, patent holder, pianist, saxophonist and singer, Eddie Harris was as broad in his interests as he was talented. Equally adept at piano, saxophone, clarinet, trumpet, vibraphone, oboe, and bassoon, Eddie enjoyed early commercial success with his jazz version of “Exodus” from the hit film of the same name (the first jazz million seller in 1961) while charting his own peripatetic path. Eddie also wrote the jazz standards "Listen Here" and "Freedom Jazz Dance," the latter popularized by Miles Davis, though Eddie seemed unfazed by his renown, as he related, "It just happened that Ron Carter took the tune over to Miles Davis and he recorded it, and then it became hip,” as did the multitude of others who performed it...

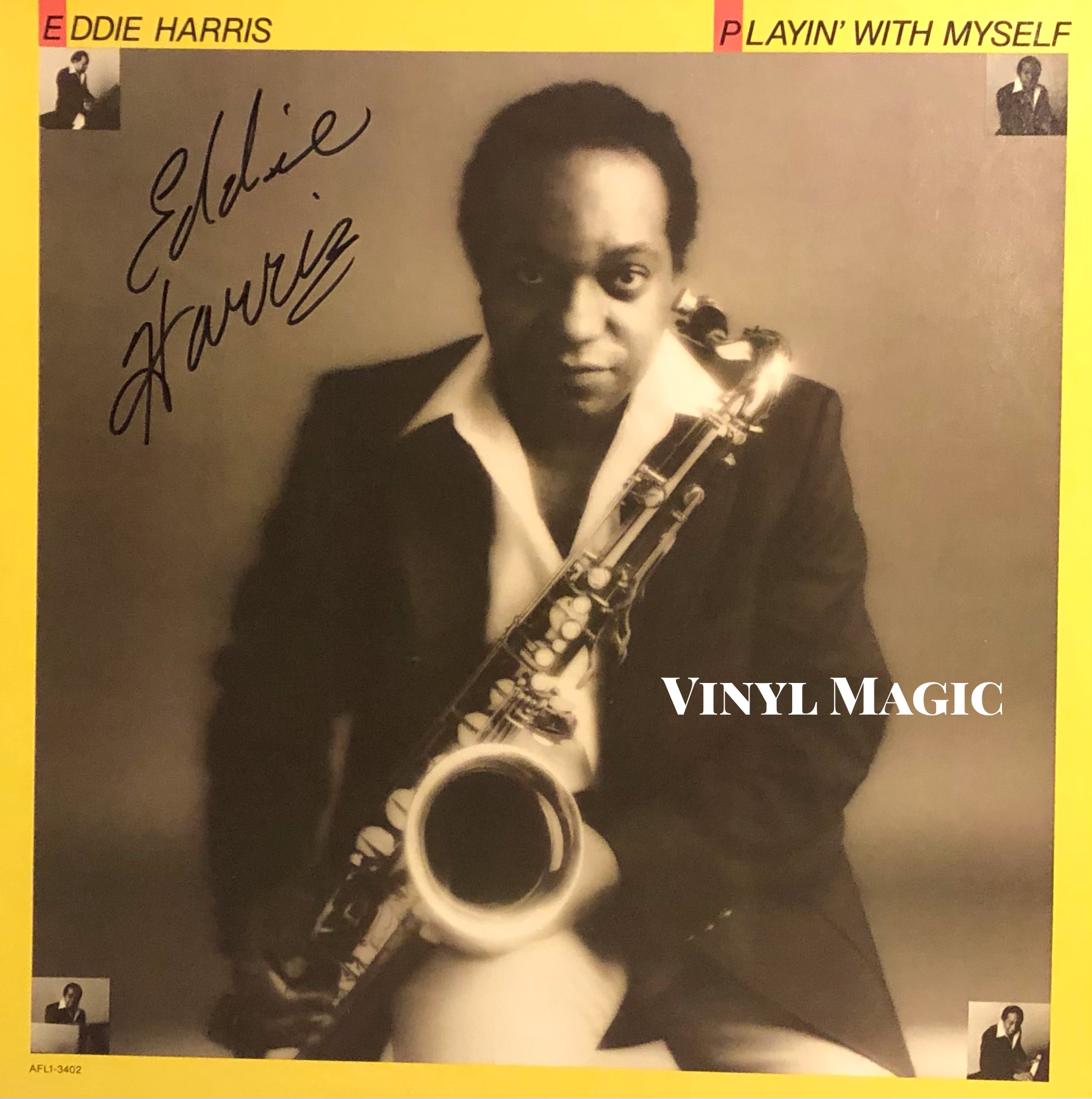

Playin’ With Myself (1979) signed by Eddie

Born in Chicago, Eddie studied music at Dusable High School under the imposing Walter Dyett who ran a fabled music program: Nat King Cole, Bo Diddley, John Gilmore, Johnny Griffin, Clifford Jordan, and Julian Priester are among its distinguished alumni. Walter Dyett was a bit of a martinet and he was unrelenting in his discipline and direction to his students, as Eddie recalled, “(Walter) Dyett was an instructor...he had been a Captain in the service, and he had to be rough, because the guys who came to that school were extremely rough. In other words, say you hit that part wrong. Some guys would just tell you, "So what? Go on and play the music," and he didn't tolerate that. He would either go upside your head, or have you bring your parents up to the school. I remember one time, I fell asleep. He kicked the chair out from under me, and I got up off the floor with my clarinet sprawled everywhere! It was really strange."

Although draconian and extreme, Dyett's techniques did have their rewards, "We could just read tremendously, because Dyett taught us like that...Woody Herman, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton - I got a chance to hear all these guys. They'd come by because they just couldn't believe the Booster Band was that hip. That was the jazz band, and when you miss a note, you're out of the band. He'd pop his fingers, 'You're out of the band, bring your mother up to school.' And a guy in the back would take out his instrument, he'd come and sit down, and he was just as good, if not better. I mean, it was that kind of competition you came up under, which really helped you."

Plug Me In (1968) unsigned

The school became a hotbed of talent for band leaders like Sun Ra (née Herman Blount) who relocated to Chicago from Birmingham, Alabama. Sun Ra was able to poach many students for his band who went on to storied jazz careers, John Gilmore and Eddie Harris among them. Sun Ra’s music was necessarily dense and different which flummoxed critics and listeners alike. Eddie remembered, “I didn’t have any adverse reaction to it, due to the fact that I played in the orchestras. I played classical music. The big thing was looking at the way he wrote them. It was like orchestra music. You had scales, arpeggios, flamadas and like that. He would write a note and make a zig-zag line to another note, and within that time frame, you played what you wanted to play. Which is modern writing today, but I wasn’t too hip to that, you know. I would have liked to stay along with him and played a lot longer, but I couldn't go along with his teachings that he had after rehearsals and after playing, when he said, 'I've been here before,' because he was talking about 'Space is the place' and going on with that. I liked his music, I liked to experiment, but I couldn't go along with his teaching. So not being with him, that's when I more or less started playing with another group of guys..where we did our thing." Eddie was far too earthy and grounded for Sun Ra’s extraterrestrial musings, and though his tenure with Sun Ra was brief, it was influential, notwithstanding their distinct philosophical differences, as Eddie would use the relentless innovation and restless experimentation in his future endeavors.

The Real Electrifying Eddie Harris (1982) signed by Eddie

After a stint in the US Army, Eddie moved to New York City and was in demand because of his versatility, playing in orchestra pit bands on Broadway, a grueling nine show a week schedule, and with trumpeter Kenny Dorham. Eventually, Eddie was frustrated with his lack of financial recompense, so he decided to move back to Chicago, "I just went back to Chicago...I was scheduled to go back to Europe and play because Quincy Jones was going to hire me to take a guy’s place named Oliver Nelson... He said, ‘Man, I’m happy to run into you. You can go back to Europe with me.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ I stopped by to see my mother, and she asked me what I was doing, and I said, ‘I’m going back over to Europe with a guy named Quincy Jones.’ She started crying. She just made a big issue out of this. I said, ‘What’s wrong? What’s wrong?’ She said, “I understood you was going to make a record.” I said, ‘Oh yeah, I can do that when I come back.’ She said, “It’s a shame. I’m ashamed to tell people that you play music because everybody’s made a record but you.” I said, ‘I don’t care nothin’ about that. I’m working. I’m playing.’ She said, “Well, you ought to make this one record, because VeeJay asked you to make a record.” But they’d asked me to record on piano, because they wanted me to sound like the guy down the street at Cadet Records who I used to show chords to... Ramsey Lewis...this guy had the Gentlemen of Jazz, and that was selling. So they wanted me to do that down the street at Vee-Jay. And I wasn’t particular about that, so I didn’t care nothing about making a record. But my mother said, “Oh, please make this one record, then you can go to Europe, Asia, anywhere.” I said, ‘But won’t nobody want me then if I stay here and make the record?’ So I went down to Chess, and I talked with them, and they said, “Well, we don’t want you to play the saxophone; you’re too weird,” and I told him where to go. Well, there was a guy named Sid McCoy, and a guy named Abner, who ran the company . . . It was actually Vivian and Jimmy’s company, V-J, and Abner was the president, and Sid McCoy was the A&R, artists and repertoire guy. Abner, who had gone to college with me, said, “I’ll tell you what. I’ll let you play several numbers on saxophone.” I said, ‘Okay, that’s fair enough.’ I told Quincy that. He said, “One record?! Oh, man.” And to this day, when he thinks about it, he says, “One record” — because that one record turned out to be “Exodus.” Isn’t that amazing? A million-seller.” Originally released as a 45 rpm single, “Exodus” went on to sell more than two million copies, and helped catapult Eddie's career which led to more than seventy albums as a leader and millions of records sold. And it wouldn't have happened without Eddie's mother's persistent and prescient admonition!

Trip! (1961 recordings, 1969 release) unsigned

All of Eddie's success came with a price, however, as critical acclaim never matched his commercial viability, "I figure that I'm put down because I sell a lot of records." That wasn't entirely true, as Eddie was unyieldingly creative and some of his albums were all over the map musically, mixing genres like funk and fusion, featuring his gruff vocals, and instruments that he helped create like a saxophone outfitted with a trombone mouthpiece that Eddie dubbed the "Saxobone." He also experimented with an electric saxophone, the "Varitone" which further confounded and alienated jazz critics and purists alike. He even released a comedy album - The Reason Why I’m Talking Sh*t - which was probably the final straw. As he admitted, "I'm experimenting. I'll try this, try that. A lot of people would say, 'No one knows where to put you.' I'd say, 'Why don't they just put me in a category called "Don't know where to put you?" You can do anything you want to do, if you want to do it." And he did.

Second Movement (1971) signed by Eddie, Les McCann

Erin and I saw Eddie only once in 1988 at Blues Alley in Washington DC. He and Les McCann were celebrating the twentieth anniversary of their album Swiss Movement, which was recorded at the Montreux Jazz Festival. An impromptu jam session, the album was mostly improvised and a last minute addition to the third annual Montreux Jazz Festival. Though Les and Eddie knew each other, they were an odd and unlikely couple. Eddie was meticulous and planned everything, Les not so much. He was as freewheeling and open to possibilities as Eddie was disciplined and structured. Their commonality derived mostly from being on the same record label - Atlantic Records - who suggested they perform together.

Even more remarkable, Eddie, Les and the band had only rehearsed for ten minutes before they "let it happen." The celebratory throng in Montreux was only the beginning as Swiss Movement went on to sell more than a million copies and became one of the finest examples of Soul Jazz when it was released in 1969. It also helped cement the reputation of Montreux Jazz which was then an unproven and fledgling festival, not the international showcase it has become more than fifty years later.

Second Movement (1971) back cover signed by Les McCann

The show at Blues Alley was a lot of fun. The rollicking piano of Les was driven by the searing tenor of Eddie. They played their biggest hit, "Compared To What" and "Cold Duck Time," a song which Eddie wrote, a paean really, about the virtues of an adult beverage of dubious quality and intent. After the show, Eddie was gracious as he signed his vinyl but seemingly withdrawn in contrast to his partner, the voluble and expressive Les McCann. We thanked Eddie for his time and especially his music.

Sadly, we never had the chance to see Eddie again as he passed away in 1996, but what a legacy of music and songs he left us. An author of seven music books, a patent holder for mouthpieces which he designed for trumpet, trombone and saxophone, and a seller of millions of records, Eddie has also been sampled by hip hop artists, Heavy D, The Notorious B.I.G., Digable Planets, Gang Starr and hundreds of others. Although the critical acclaim may have been elusive to Eddie during his lifetime, his influence and relevance extends among fans and musicians to this day. Maybe, just not for his comedic efforts, that record is rare to find and deservedly so.

The In Sound (1965) unsigned

Choice Eddie Harris Cuts (per BKs request)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4HJjnHiMVhw

“Exodus” Exodus To Jazz 1961

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CsHtO_i4qzM

“Listen Here” The Electrifying Eddie Harris 1967

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iDrH5urtCbQ

“Freedom Jazz Dance” The In Sound 1965

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7F7sg5IeZY

“My Buddy” Mighty Like A Rose 1961

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kCDMQqDUtv4

“Compared To What” live at Montreux 1969

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8YOLY4Tats

“Cold Duck Time” live at Montreux 1969

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DRIRtrw-rsE

“The Shadow Of Your Smile” The In Sound 1965

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Az34xP65Fn4

“Set Us Free” Second Movement with Les McCann 1971

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cXT23pOH7g

“I Don’t Want No One But You” The Electrifying Eddie Harris 1968

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DgqdT9iYHxM

“Playin’ With Myself” Eddie plays piano and sax 1979

Bonus picks:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJ11cArknek

Miles Davis: “Freedom Jazz Dance” Miles Smiles 1967

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hzelqRLyIlg

Dr. Lonnie Smith: “Freedom Jazz Dance” live 2008

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4R2qZFC4Qb0

“What I’m Thinking Before I Start Playing” The Reason I’m Talking Sh*t 1975