Charles McPherson, Mingus, and Me…

I remember coming over to his house one day, and I had my report card with me. He said, 'Hey, let me see your report card.' So, I showed him the card. Now, in those days I was a “C” student; I had no As, no Bs on my card. I didn’t do much to try to get an A; as long as I got a C and I was passing and wasn’t the dumbest guy in the class, I was fine with that.

When Barry saw all of those Cs, he looked at me and said 'You’re quite ordinary!' I didn’t think of that as being a put-down or anything like that. Then, he said, 'I’ll tell you; the kind of musicians that you like, and the people that you admire, these people are not “C” students at all. They are very special people. You can’t just be a “C” level, mediocre and ordinary person and have just a mediocre mind to play this kind of music. It’s too complicated; there’s too much stuff going on, and you’re not going to be successful with it. You need to do everything that you can to broaden your mind. How you think, how you conceive and all these things. You need to get a new template other than this “C student” thing.'

When he said that , it meant more to me coming from him than coming from my parents saying the same thing. From that point on, I started doing the New York Times crossword puzzle because Barry did it. He would do the Sunday puzzle in an half hour. Besides music, he was a voracious reader; he would read books about Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. I had no clue about any of that kind of stuff.

Charles McPherson on lessons with pianist and mentor Barry Harris

Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (1964) signed by Charles, George Coleman, Benny Golson, Richard Wyands

I stayed a long time with Mingus, about twelve years. Drove me completely nuts! I quit for about a year, worked for the Internal Revenue Service because I had kids. I was like, ‘Man, Mingus, I can’t.’ He was a great musician but…gone…you know? I told myself I have to get away from Mingus. So I went to the Internal Revenue and I worked on 1040s. That was weirder than Mingus... I did it for about a year. It was interesting – I saw a lot of returns. I remember seeing John Coltrane’s return one year. This guy was making serious money. That was amazing to me in the sixties. A jazz tenor player and this was during his tour of My Favorite Things with the soprano and Greensleeves. I actually did his return – I saw it! I thought a tenor player playing jazz, making that kind of money. in 1964 or whatever, was pretty impressive.

Charles McPherson

Tijuana Moods (1957 recordings, 1962 release) signed by Charles

In working with him, as difficult as he could be, I found out that he had a good heart. There was a tenderness about him in his heart, and he was honest; he wasn’t a dishonest man. This part of Mingus that never gets out, I saw. As a case in point, we were doing a benefit for a beat poet and writer named Kenneth Padgett.. He was a personal friend of Mingus and he was sick. We were in Mill Valley and we did a benefit with Mingus' Band. At the end of the benefit, Mingus started handing out $5 bills to us. He wanted to give us something, because we were playing with no salary. Everyone took the five dollars, except me. When he got to me, I just said to him, 'What's five dollars, more or less? Just put it into the kitty for the man because he's sick..Five dollars is not going to change my life, so give it to him.' I was about twenty. When he saw that everyone took the money except me, he looked at me and his eyes got all welled up with tears, and he said, 'Thanks Charlie.' From that point on, he had a different way of dealing with me than he did with everyone else in the band. He was moved that I, a twenty year old, gave back the money. That impressed him. He had a special way with me. I could be late, or act kind of silly on the bandstand, but he would just kind of look the other way and wouldn't give me a hard time...

Charles McPherson on Charles Mingus

Mingus At Monterey (1965) signed by Charles, Richard Wyands, Jon Faddis

Born in Joplin, Missouri, and raised in Detroit, Charles McPherson is an acclaimed alto saxophonist, arranger, and composer. Appearing on more than seventy albums as a leader and side man, Charles is probably best known for his twelve year association with Charles Mingus. Charles recalled their beginning, "I came to New York in 1960. I started working with Charlie Mingus..He was different than Detroit guys but he did have this: he wrote poetry, he painted, he had a world view, and he was totally into music. These people were bigger than life. They were just characters, they were really something, that generation."

Con Alma! (1965) signed by Charles

Equally formative was Charles early upbringing in Detroit, a thriving jazz scene in the 1940s and 1950s. Charles remembered his lucky circumstances, "The street that I lived on just happened to be a street where Barry Harris lived right around the corner, five minutes away. A trumpet player named Lonnie Hillyer, who worked with Mingus along with myself for a long time, lived right on my street. And there was a jazz club a few blocks down on my street called the Blue Bird, which was, at that time, probably the hippest jazz club in Detroit. So it was interesting that, of all places, as big as Detroit is, I ended up on the same street as a really great local jazz club. The house band at that time was Barry Harris on piano, Pepper Adams playing baritone sax, Paul Chambers or Beans Richardson on bass, and Elvin Jones was the house drummer.” Some house band, nearly all these artists went on to lead and perform on seminal jazz albums throughout their outstanding and prolific careers.

Bull’s Eye (1966) signed by Charles, Barry Harris

After being told about Charlie Parker by a tenor sax student in his junior high school band, Charles' life was transformed, "One day I was in a little candy store, and there was a jukebox with records in it, and I saw Charlie Parker. And I was like ‘Oh! Let me put my money in and hear this guy!’ And when I heard that “Tico-Tico” (from Charlie Parker South of the Border), I was completely floored. I was thirteen or fourteen years old, and from that point on, it was like ‘that’s it.’ And I knew nothing about changes or chords, and I’m just a kid. I knew immediately that this is the way you’re supposed to play.” Augmented by regular visits to the Blue Bird club down the street and, especially Barry Harris' house, Charles musical education flourished. "It was a big lesson. At that time, Barry’s house was a hub of musical activity. Everybody in the city, all of the good musicians would come over to Barry’s house because he worked at night, but in the day time, he was free to practice and do what he wanted to do. Anytime anyone wanted to, they could come by and talk music, play or talk about ideas. So this was a natural thing that would happen with Barry. Musicians from New York would come by Barry’s house, as he had a reputation as an “open house.” So, I was able to see and meet John Coltrane; he would come by Barry’s house when he was coming through from New York. Sonny Rollins…all of these wonderful people. And I was always there, living right around the corner. After school and after homework, I would go over to Barry’s house..." Yes, Barry's lessons and "open house" served Charles well.

Stay Right With It (1972) signed by Charles, Barry Harris

As the music of Eric Dolphy and John Coltrane became more experimental and dissonant in the 1960s, Charles did not follow in their iconic footsteps, although he did replace Eric in Mingus’ band. As he revealed in a 2016 interview, "I don't think that I ever knew what Eric was doing, but I did understand, at least to some degree, what Trane was doing... I still wanted to play melodic music. I always thought that dissonance and melodicism should be balanced in music, and even how you improvise. I never thought that everything dissonant for the sake of dissonance was the way that I wanted to go. I always believed in a balance of melodicism mixed with tension and dissonance."

Bird (1988 soundtrack) signed by Charles, Jon Faddis

In 1988, noted film director, actor and jazz enthusiast, Clint Eastwood came calling. Jazz music and musicians have always featured prominently in the Eastwood oeuvre, from Erroll Garner's "Misty" in Play Misty For Me, to Lalo Schifrin's Fender Rhodes fusion in Dirty Harry, to alto sax extraordinaire Art Pepper solos in The Gauntlet. The soundtrack to Bird was no exception, and featured Charlie Parker's original solo sax recordings with a newly recorded rhythm section, including Monty Alexander and Barry Harris on piano, Ray Brown and Ron Carter on bass, and John Guerin on drums. Charles McPherson added a blazing alto on three tracks and Jon Faddis supplied a fast and furious trumpet. A technological achievement, it is a remarkable refresh on probably the most important and influential jazz artist ever, Charlie Parker (with apologies to Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington!). And, for me, the soundtrack is the best thing about the movie, which I found depressingly dark and dour, though accurate. There is nothing funny about Bird's descent into addiction and death, no MTV Behind The Music arc of downfall and then redemption. Just as Clint wanted to portray, Bird shows the inexorable decline and degradation of active addiction. Me, I'm happy to listen to the soundtrack, hard pass on watching the movie again.

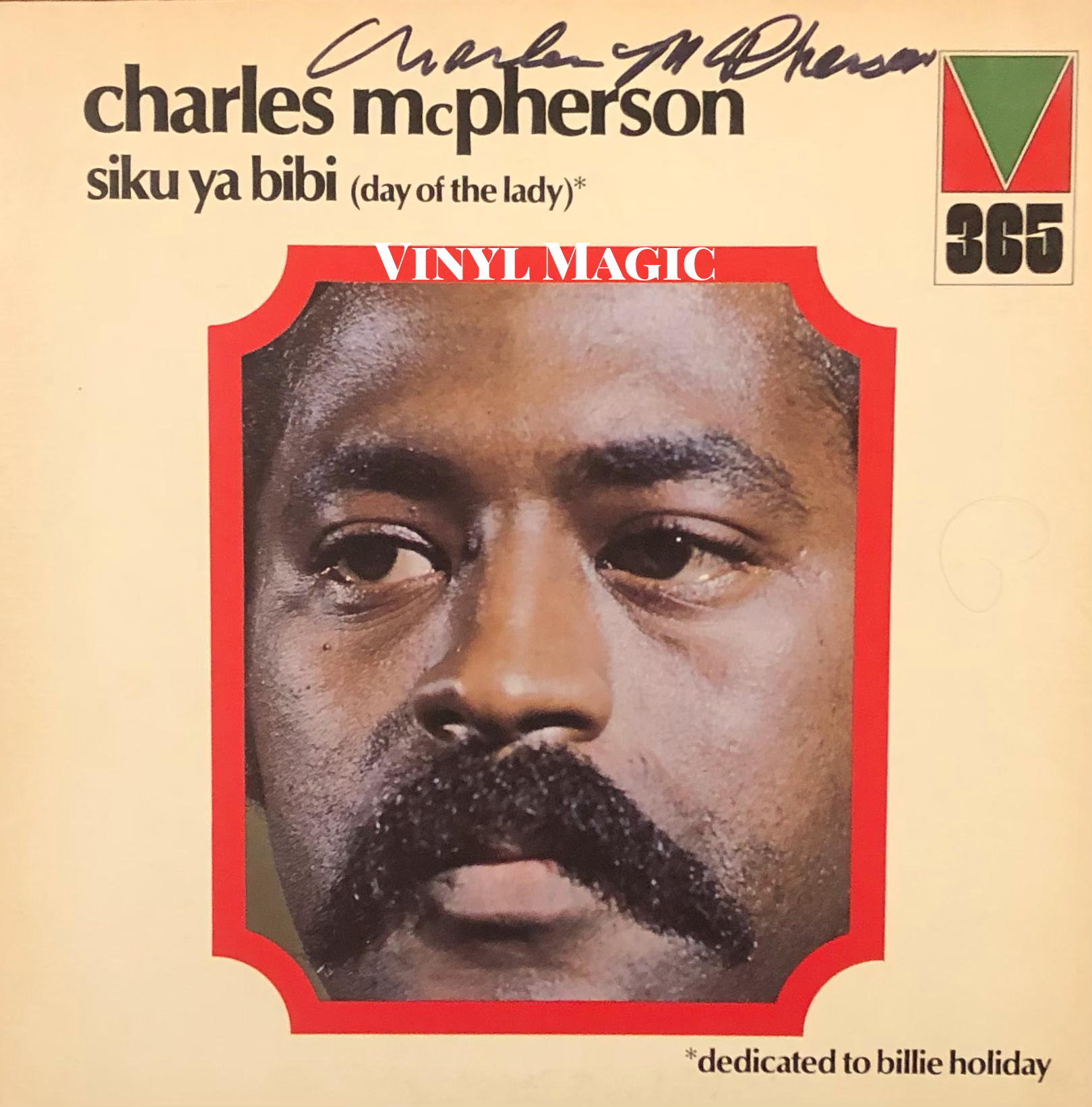

Siku Ya Bibi (1972) signed by Charles

I saw Charles McPherson perform recently at Dizzy's Club at the sprawling complex that is Jazz At Lincoln Center In New York City. Dizzy's Club is the smallest of the three venues, probably seats for one hundred-forty patrons. The backdrop is Columbus Circle with the bustling lights of New York City and Central Park twinkling below. The quintet was introduced by public address and then Charles bounded on stage and tore into a five minute solo on the Charlie Parker favorite "I'll Remember April." It was a virtuosic display of hard bop blowing from a master. For a man approaching eighty, Charles showed no signs of slowing. Next came, "A Tear And A Smile", a luxurious ballad that showcased Charles' strength of melody and improvisation, and "Marionette", another McPherson original, highlighted the extended guitar work and crisp, disjointed leads by guitarist Yotam Silberstein. A beautiful ballad, "Yesterdays", followed with Charles' warm and resonant alto rendering the composition with grace and emotion. "Lester Leaps In", the Lester Young composition by way of Count Basie galloped at breakneck speed with a drum barrage by Johnathan Blake and percussive comping by pianist Jeb Patton.

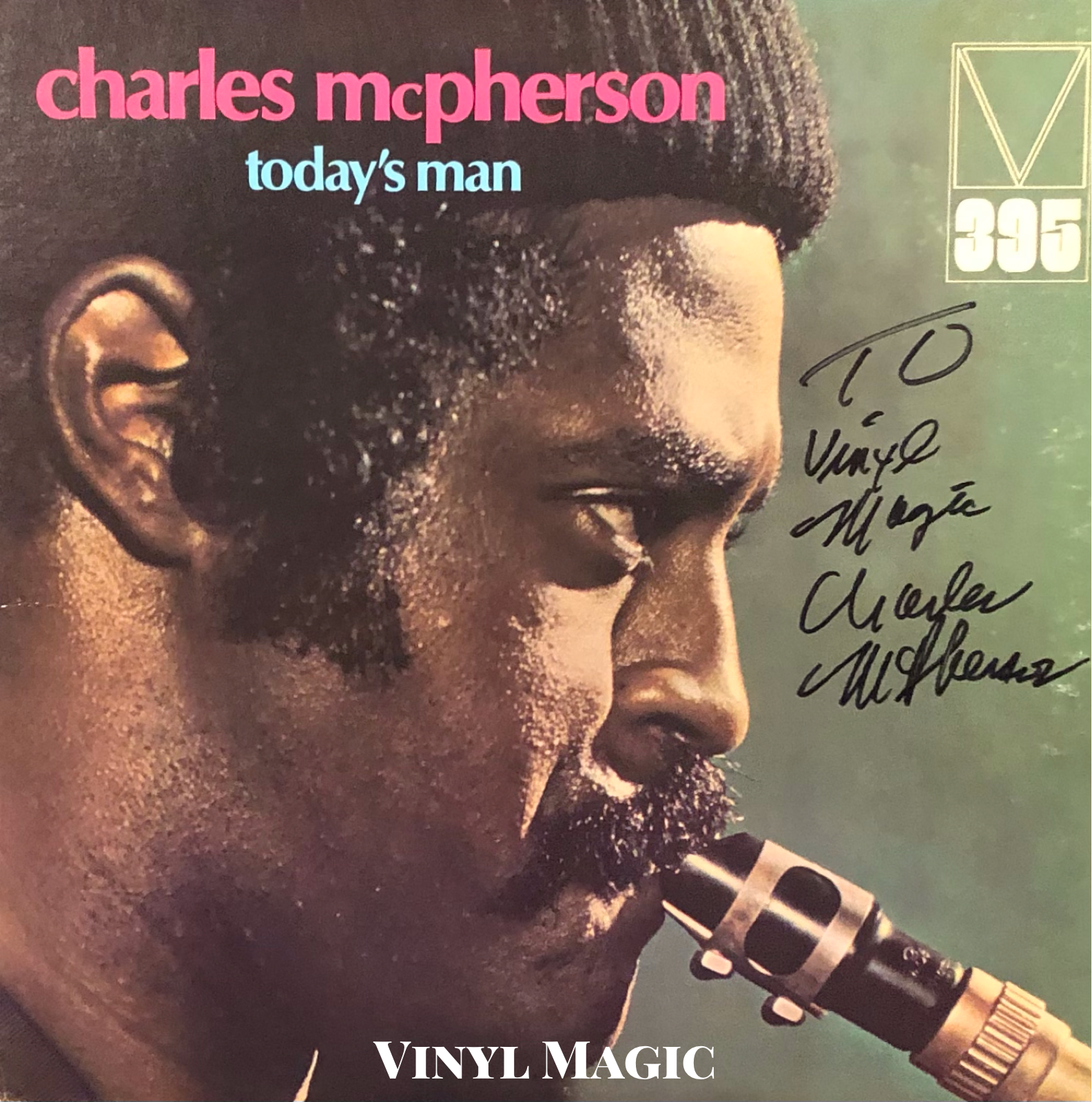

Today’s Man (1973) signed by Charles

For an encore, Charles introduced "Blue Monk", a Thelonious composition with "We always need to have some blues in our program," and he began to lay out a mournful, soulful sound which the band leisurely followed. As Charles said recently, "The real vibe of the blues - a slow blues, not an uptempo blues - is a state of reverence. The Greeks had different words for different kinds of love. "Eros" is sexual love. "Agape" is more how you feel about God. In the blues, even though there's plenty of suggestive lyrics, the feeling underneath is more Agape. There's a longing towards God. You have to be in that kind of space to play the blues well." Judging by the rapture evident in the club, Charles took us all to a happy place. It was a happy ending for all.

Mingus At Carnegie Hall (1972) signed by Charles, Jon Faddis

After the show, I visited with Charles. He was as lively offstage as on. I mentioned how impressed I was with his performance and stamina. It seemed as though the band is half your age and they were barely able to keep up. He smiled and laughed, "Well, thank you. I have a great band and they really inspire me." When he signed Bull’s Eye, he marveled at the band members, “Look at that rhythm section: Barry on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, Billy Higgins on drums. Man, those cats could play!” I mentioned that it was a shame that Paul Chambers died so young (age thirty-three). “Well, look at all the music he left behind. We weren’t cheated,” Charles said brightly. Next, I asked Charles an impossible question: what was your favorite band? “Oh man, that’s really hard to answer. I guess both of these for different reasons,” he said pointing to the Charles Mingus and Barry Harris vinyl. “Mingus for his Duke Ellington compositional skills and ability, and Barry Harris for his sense of rhythm, which was impeccable. I learned so much from both of them.” I thanked Charles for his time, and especially the music.

Charles McPherson, a tour de force on stage and off.

Newport In New York ‘72 (1972) signed by Charles

Choice Charles McPherson Cuts (per BKs request)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8sTexZBr-4o

"My Cherie Amour" McPherson's Mood Charles swings Stevie! 1969

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b1VihvFzcNU

"Desafinado" Live In Tokyo 1976

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=33ZF9LMGM2c

"Don't Explain" Siku Ya Bibi 1972

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i41fkEg-x40

"Never Let Me Go" The Quintet/Live! 1966

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdfpD8Z5VbM

"They Say It's Wonderful" Beautiful! 1975

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WyrY20rZjZ8

"I'll Never Stop Loving You" But Beautiful 2005

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QzdBAFKgyng

"Marionette" Come Play With Me 2008

Bonus cuts:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IguEshhurq8

"Tico Tico" Charlie Parker 1951

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tds9pKRuIhE

"Ellington Medley" Mingus at Monterey 1964

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5fiqK5Wlv8A

"In A Mellow Tone" Mingus: The Complete Town Hall Concert 1963

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SB_wYEvmU8I

"Don't Be Afraid, The Clown's Afraid Too" Mingus: Let My Children Hear Music 1972

Charles live at Dizzy’s, March 13, 2022

Charles with pianist Jeb Patton, Dizzy’s, March 13, 2022

Charles with Terrell Stafford, Dizzy’s, March 13, 2022

Charles with Terrell Stafford, Dizzy’s March 13, 2022

Charles McPherson Dizzy’s, NYC March 3, 2018

Charles McPherson and friends, Dizzy’s, NYC March 3, 2018

Charles McPherson Dizzy’s, NYC March 3, 2018