Monty Alexander and Me…

My folks were lovers of music, and l just gravitated to music from I was very young. Four years old I started to pick out tunes on the piano and I heard local musicians playing, and I just got totally knocked out that anybody could make a sound from an instrument, whether it was a guitar or a banjo or a clarinet. It didn’t matter, so I grew up with music all the time.

Monty Alexander

Alexander The Great (1964) signed by Monty

I enjoy dealing with my identity issues, the identity issue of when you’re born in Jamaica you have such a powerful and thoroughly wonderful experience in that world. The thing about the lifestyle, as well as the music thing that happens, which is a strange concoction of things that came out of Jamaica and became popular. We like to say, the rhythm is the thing. You know that feeling in the music is so strong, so powerful, it affected the whole world. Call it reggae, or ska, the whole spirit of Jamaica. And that is in me just as deeply as when I hear jazz. So what I had to do, because I was born diverse—because I’m multi-cultural, multi-racial, all the things people talk about—I love serious forms of expression... and if I play a Jamaican oriented piece, that’s going to have life in it. If I play a bluesy thing which I also heard from the time I was a kid, it’s going to have life in it. If I play a ballad like a Nat Cole song, it’s going to have life in it. I love all these things. I finally came to terms. I’m not going to try and fit in to the status quo of being a jazz musician. I don’t know what that is. I just go play. And if I have an opportunity to play for those people who have never even heard of Louis Armstrong, I’m going to move them.

Monty Alexander

Spunky (1965) signed by Monty

It's me trying to instrumentally talk about a man who come from basic, simple, no trimmings, very underprivileged and creating such beautiful music for the whole world. And because of his spirituality when he gave out his messages, people were not just listening to songs and nice melodies, no, they were affected by it.

Monty Alexander, playing the music of Ras Bob Marley

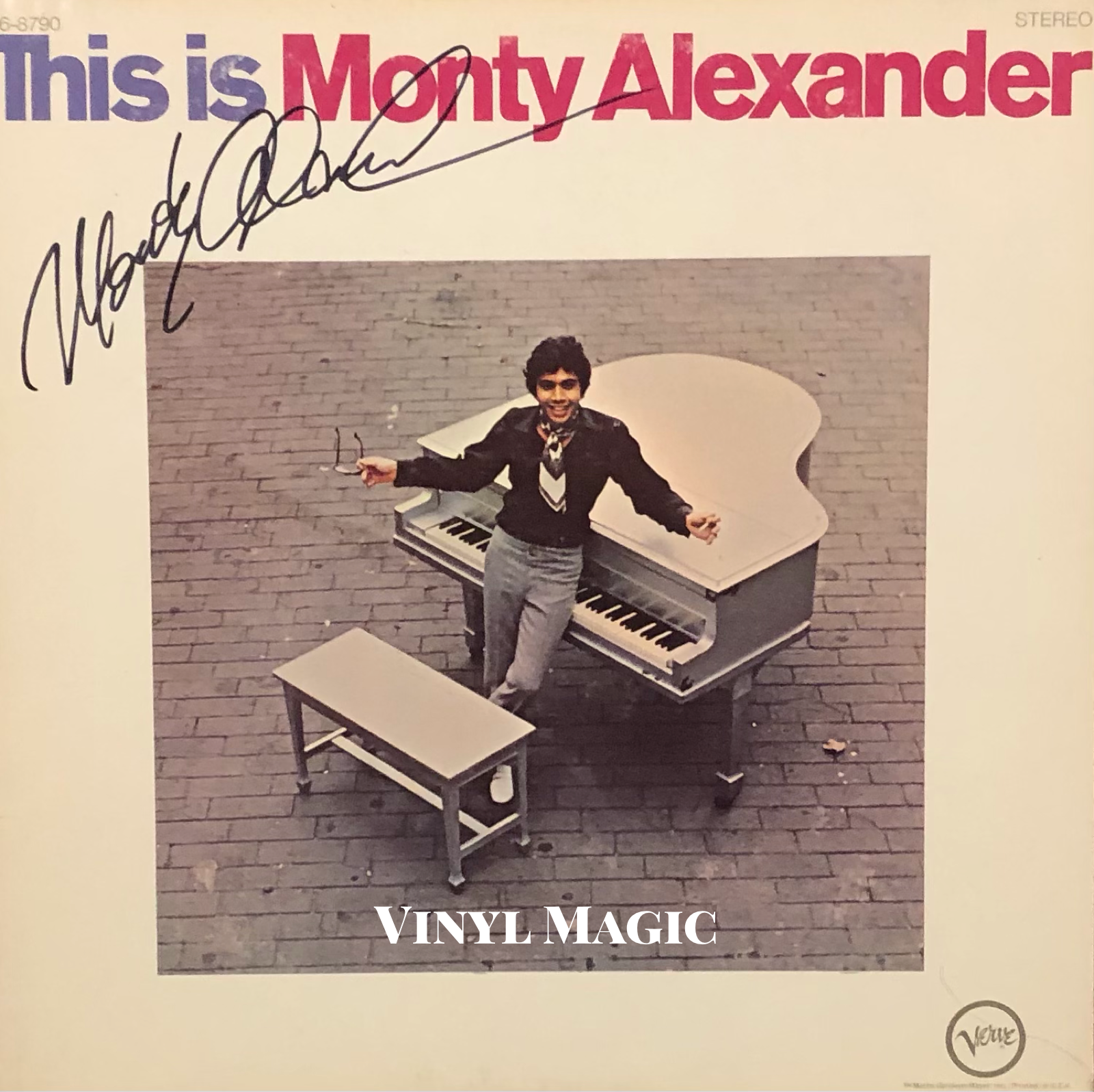

This Is Monty Alexander (1969)

Us so-called jazz musicians what we might be accused of doing or celebrated for doing is that we take our own music but certainly we get any piece of music and we're not just gonna record it or perform it exactly like it is. We can't even do it if we tried because there's this little bug in us called ‘make it up.’ I call it ‘make it up,’ they say creativity.

Monty Alexander

Here Comes The Sun (1971) signed by Monty

I soaked up everything—the calypso band playing at the swimming pool in the country, local guys at jam sessions who wished they were Dizzy and Miles, a dance band playing Jamaican melodies, songs that Belafonte would have sung. I was fully aware of the rhythm-and-blues, my heroes on piano were Eddie Heywood and Erroll Garner, and, above all, Louis Armstrong was my king. I had one foot in the jazz camp and the other in the old-time folk music—no one more valuable than the other.

Monty Alexander

Just The Way It Should Be (1969 recordings, 1973 release) signed by Monty, Ray Brown, Teddy Edwards, Milt Jackson

Somebody I admire and respected a lot talked to me almost like I was an older brother, and it was none other than Ray Brown, who invited me to join him and Milt Jackson on a job in 1969 at Shelly's Manne-Hole. He saw that I was playing here and playing there. I'd already made about eight albums. "You know, you should try playing with some younger guys," he said to me. So I would play with these different guys, all the great bass players, 'cause I was already in that world and I knew what to do. I was leading the troops, if you know what I mean. I always had my own combo. I wasn't playing in somebody else's band or anything. I would get a gig and hire whoever it would be. In New York, I had engaged all these greatest bass players and drummers. So many of them—Ron Carter came to play with me, Roy Haynes came to play with me, Tony Williams. Just name it, a crew of different musicians. They were older than me, guys ten years older, and they didn't tell me what to do. They were following me.

So Ray said, "you should play with some younger guys," and I said "OK." That was when he introduced me to one of these up-and-coming younger bass players named John Clayton. John was just going to school and he told me about this friend from school, Jeff Hamilton. And they'd never played with people who hadn't gone to school. I came up with guys playing at functions with their friends, you know. We called it the university of the street corner. Most of our heroes of jazz were salt-of-the-earth guys who picked it up from one another. So, years went by and John stayed in touch with me. He came out of college, and he called at the exact time I was looking for a bassist. That all started with him and from that point on, I realized "hey, I'm playing with these whippersnappers." Since then, I like musicians who are younger.

Monty Alexander

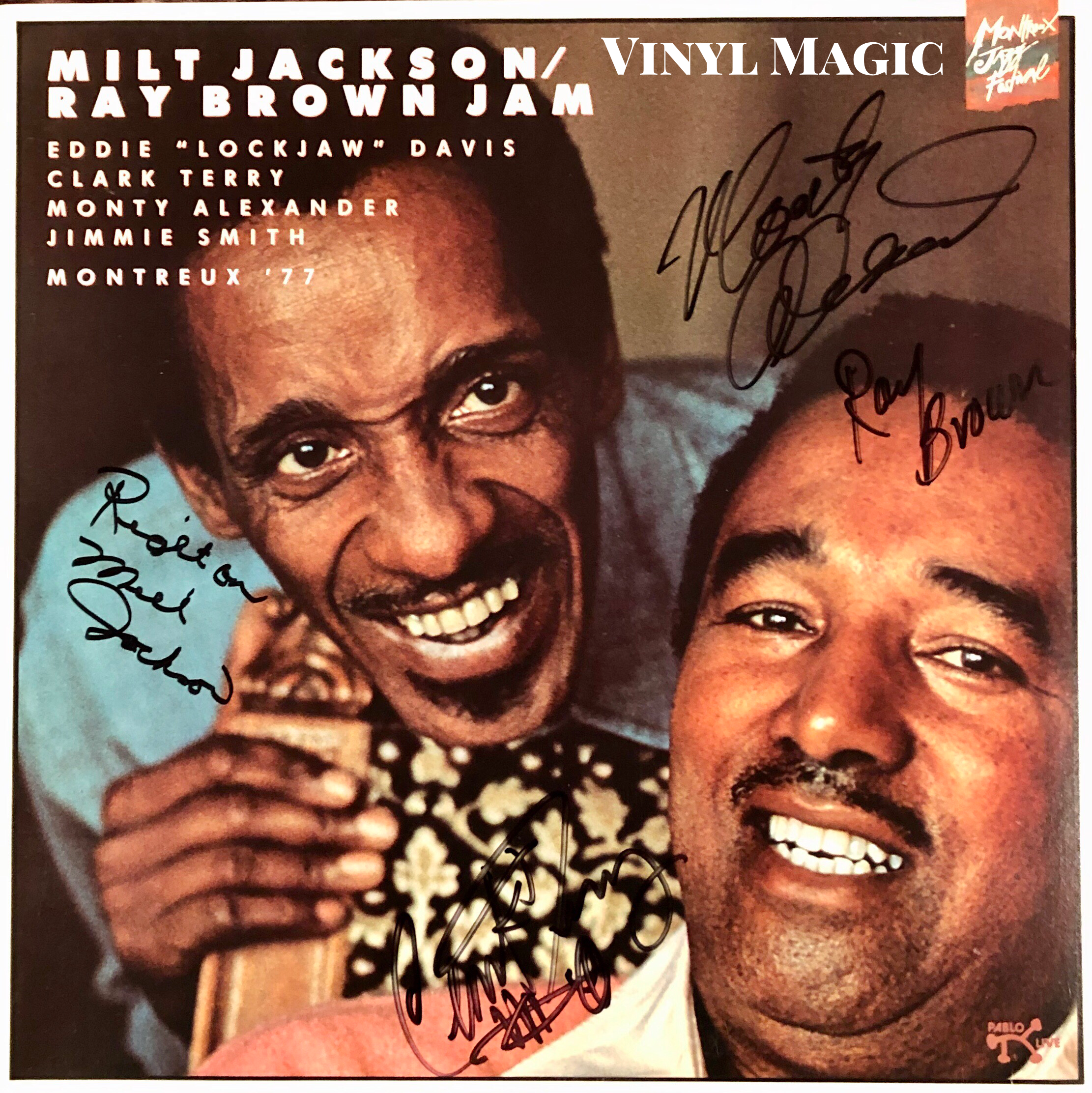

Montreux’77 (1977) signed by Monty, Ray Brown, Milt Jackson, Clark Terry

Well, I have this whole philosophy. Whether you're playing for a small crowd or a large crowd, a small place or a large place, it's all the same thing. It comes from your innards, down in the gut, the spirit. Something comes out and people say, "how'd you play that?" I say "Man, I don't know." It's a magical thing. It's a mystery. That's one thing, one problem I have a lot with music teachers. A lot of them say, this is what it is, that's what it is. It's the same with preachers. I'm more drawn to the guy who says, I wonder what it is. What is it, question mark? How did this happen?

Monty Alexander

We’ve Only Just Begun (1971) signed by Monty

Born in Kingston, Jamaica, Monty Alexander studied classical piano as a six year old until he discovered jazz as a teenager. When he saw Louis Armstrong perform in 1957 at the Carib Theater, Monty was never the same. He started hanging around local musicians and sitting in on recording sessions. As he recalled, "The musicians in Kingston where I grew up were really so hospitable and friendly and warm and wonderful. I would go from place to place and hang around and pretty much terrorize every musician - 'Hey man, I love music. Can I play? Can I sit in?' And little by little I would be welcomed to join in with different groups playing. That's how I got involved with the recording studios because even at thirteen or fourteen years old, I used to sneak out of school. I would just say, 'I don't wanna be in school. I want to be where the musicians are.' And I'd go to the studio and that's how I started recording and I ended up making a lot of recordings back in the late 50s/early 60s for the producers at the time, people like Coxsone Dodd and Duke Reid..."

Duke Reid: Golden Hits (1969) signed by Monty

Although his performances were uncredited on those early Studio One sessions, Monty formed lasting friendships with the musicians, especially trombonist Don Drummond (a founding member of The Skatalites), saxophonist Roland Alphonso and guitarist extraordinaire Ernest Ranglin (they released nine albums together!). Ranglin remembered Monty's early days. "This guy, from the first time I hear this guy, we don't have to invite him up (on stage), we were dying to get him up." To which Monty responded, "I remember one thing. I came with plenty of enthusiasm. Rather than being light and right, I was wrong and strong!" This was a simpler time in Jamaica, the languid beats and shuffle sounds of "Ska" and "Rocksteady", well before Toots & The Maytals recorded "Do The Reggay" in 1968 which helped usher in the reggae explosion. While the Toots' song gave the music a name and genre, the "Reggay" dance craze did not endure. But the music of Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer which followed certainly resonates. Everywhere.

Smackwater Jack (1971) signed by Monty, Bob James

Monty's family moved to Miami in 1961, and a year later he moved to New York City where he became the house pianist for Jilly's, a Frank Sinatra hangout in the 1960s run by Jilly Rizzo, a Sinatra crony. There, Monty often performed with Frank when he came to visit New York and received valuable exposure. In 1964, Monty recorded his first album and he has since recorded more than seventy albums as a leader and many more as a sideman with Milt Jackson, Ray Brown, Herb Ellis, and Dizzy Gillespie. And in the last decade, Monty has revisited and re-explored his Jamaican roots on additional recordings with Ernest Ranglin which showcase the compositions of the sine qua non Bob Marley, but also the talents of "Toots" Hibbert, Augustus Pablo, and Burning Spear (aka Winston Rodney). One memorable performance I saw in the early 2000s was Monty's solo rendition of "Redemption Song", an exquisite homage to Ras Bob, flawlessly and elegantly played.

With Love (1971) signed by Monty

I saw Monty perform again recently at the Blue Note in New York City. He was playing a week long gig that showcased his many talents and versatility. The first two nights Monty performed with a quintet as a tribute to his early recordings with Ray Brown, Milt Jackson and Teddy Edwards, the second two nights with his trio celebrating their 40th anniversary, and the last two nights with his Harlem-Kingston Express, a reggae inflected juggernaut investigating the sounds of Marley and other island rhythms. I opted for the trio format with John Clayton on bass, Jeff Hamilton on drums and Monty on piano, and I was not disappointed in their virtuosity.

Ivory & Steel (1980) signed by Monty

They opened the set with a bright and bluesy "Satin Doll" from the Duke Ellington songbook, a song which the trio first recorded in Montreux in 1976. They sounded great; Monty ripping off thunderous runs with either hand, John Clayton providing a sturdy bottom with his bass, and Jeff Hamilton dropping precise beats and accents with brushes and shimmering cymbals. Other song highlights were Cole Porter's "Love For Sale" which Monty wove into his composition "Think Twice", a delicious and delightful juxtaposition, and "Sweet Lady", a ruminative ballad which lived up to its name.

Love And Sunshine (1974) signed by Monty

The most interesting song transformation was "Ben", made famous by Michael Jackson in the 1972 eponymous movie. "Ben" was a Number 1 pop hit for Michael Jackson and it was nominated for an Academy Award (it lost to "The Morning After" from The Poseidon Adventure). Not surprisingly, the movie garnered far less acclaim. Following a luminous bowed bass introduction by John Clayton (evocative of the cello of Yo Yo Ma), Monty and his trio refashioned "Ben" as chamber jazz which then settled into a mid-tempo groover. It made me forget the abhorrent movie from whence it came: a sequel to the equally distasteful Willard. I guess killer rats were never my thing no matter how dressed up as a horror or morality tale! The trio's finale was the oft recorded "The Battle Hymn Of The Republic" which began as a soulful, mournful gospel and, by skilled turns, became a rollicking, swinging romp. It was a fabulous end to a fabulous night of music.

Triple Treat (1982) signed by Monty, Ray Brown

After the show, I visited with Monty, Jeff and John upstairs near their dressing rooms. As warm and genial as Monty is on stage, he is equally kind and generous off stage. There was quite a crowd of fans and well wishers surrounding him, and he was happy to sign my vinyl. I handed him Soul Fusion, a Milt Jackson album recorded in 1976. Monty saw Milt's signature, paused and said, "You know, I miss Milt more than ever. We made some great music together." I mentioned how much I liked his treatments of Bob Marley, especially "Redemption Song." "Bob is my man", he said quietly. I told Monty that I loved his version of "Ben" but that I hated the movie and the song. He laughed, "Yes, that's what we try to play, songs that most people hate!" Rather then try to explain my faux pas, I decided to cut my losses. It was time to move on.

Soul Fusion (1978) signed by Monty, Milt Jackson, Jeff Hamilton, John Clayton

His band mates, John Clayton and Jeff Hamilton were equally kind. John Clayton drew a little bass figure on the cover of Soul Fusion, and apologized when he got bumped by a passerby. I told him that many have his signature, but no one has that signature. The bump made it more valuable, it is sui generis! Jeff Hamilton was also very solicitous when I handed him Soul Fusion. He saw Milt Jackson's signature and said, "it is a great honor to sign anything that has Milt Jackson's name on it." I apologized, "I'm sorry there's not much room on the cymbal, the other fellas signed most of it." Jeff replied, "As a drummer, that is very appropriate. You know, that is a very important cymbal. It was given to me by John Van Ohlen when I was studying with him at Indiana University. John tried out for Benny Goodman but he didn't make the band. He gave me that cymbal to go and make it. And that recording with Milt is when I made it." I was happy that Jeff found room above Monty's signature to add his signature, and he also signed Facets, his wife's favorite album. "You know, this album is about the only recording of mine that makes her playlist and she is more than happy to tell me that," he confided with a smile.

Facets (1980) signed by Monty, Jeff Hamilton

Monty Alexander, a fabulous pianist whether performing solo, with his trio or a reggae band. He said recently about his reggae recordings, "I'd go to the studio with Sly (Dunbar) and Robbie (Shakespeare) who know me from way back. It's simple music, two chords - but life is in those two chords."

Thanks for all the chords, Monty. There's so much life and love in all your music.

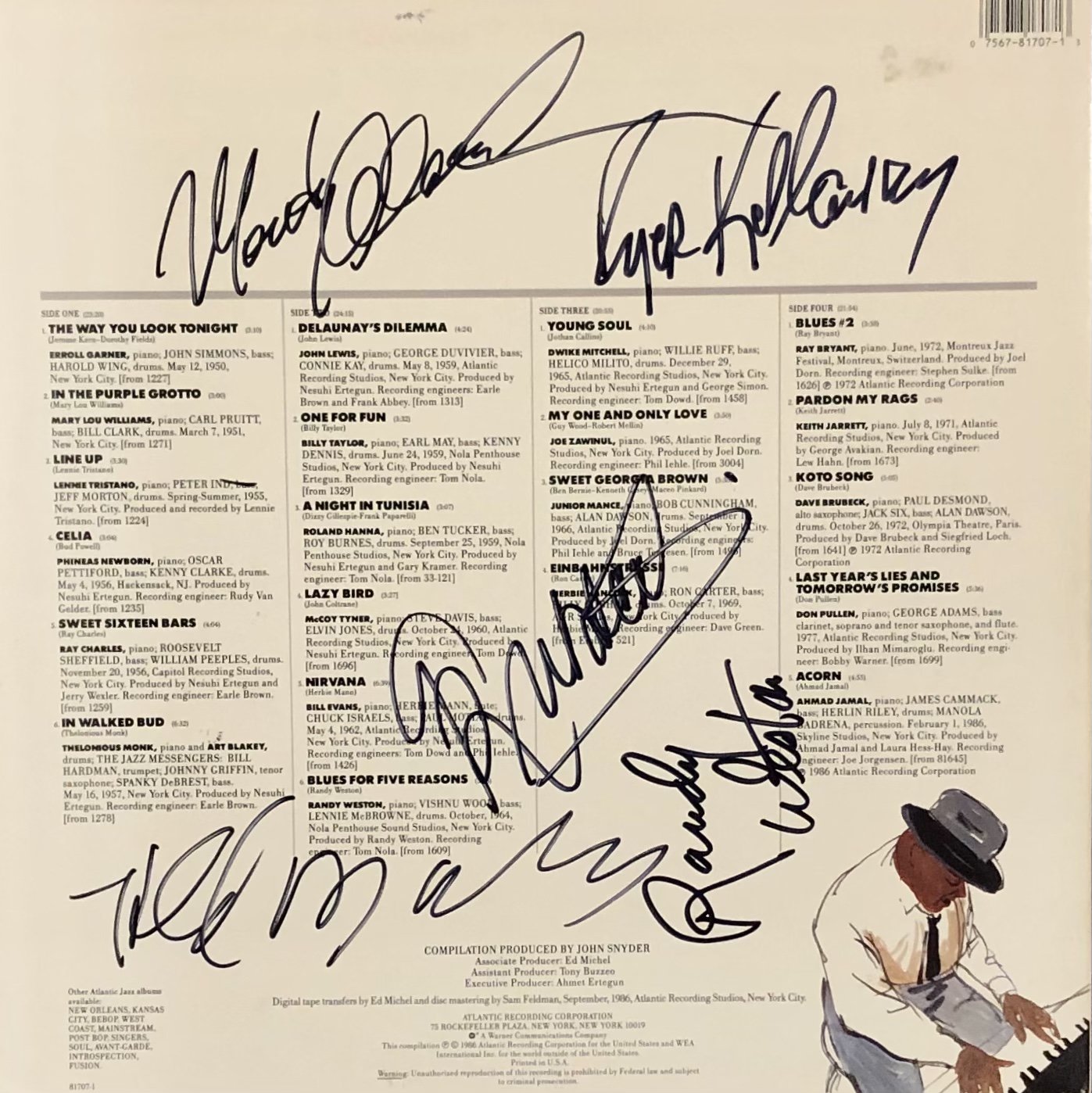

Atlantic Jazz Piano back cover signed by Monty, Harold Mabern, Roger Kellaway, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Randy Weston

Choice Monty Alexander Cuts (per BK's request!)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVB1NB8lvqM

"Redemption Song" Rocksteady 2004

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ApmNziTwU6g

“No Woman No Cry" Harlem-Kingston Express Live! 2011

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ycOeXVjWRM

"The Battle Hymn Of The Republic" Perception 1974

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=20rH1NroT00

"Ben" Perception 1974 Monty swings Michael!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2xtUrS26y4

"What A Friend We Have In Jesus" Monty Takes Us To Church! Live 2011

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vYMYFViAQJY

"Satin Doll" Live Montreux 1976

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_D4_apFuT8

"Sweet Lady" Triple Scoop 1987

Bonus cut:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JJwfh2TbmJg

"Do The Reggay" Toots and The Maytals 1968

Full Steam Ahead (1985) signed by Monty