Benny Golson and Me...

I went to see Lionel Hampton in 1945 at the Earle Theater at 11th and Market St. in Philadelphia. It was the first time I had seen a live band. I had started playing piano at age nine and fancied I'd become a concert pianist one day. But during the Hampton concert, the band played an intro and Arnett Cobb stepped out from the reed section to the front of the stage with his tenor sax. A microphone came up out of the floor, and Arnett started playing "Flying Home." At that moment, the piano for me started to lose its appeal. I told Arnett years later in Nice, France, that he was the reason I was playing the tenor sax. Tears welled up in his eyes.

Benny Golson

Jazz Sahib (1957) signed by Benny, Hank Jones, Phil Woods

John (Coltrane) and I were like blood brothers. I was 16 when I met him — he was 18. And we spent our time in my living room, listening to lots of 78 [rpm] records, trying to figure out what was going on. And we had a beat-up piano in the corner, and I'd play after a fashion, while he played. And he played worse than I did — for me. We really annoyed the neighbors. We were in the front room, and it was summertime ... but we knew we were getting better. My mother would go to the market, and after a few months, we were getting requests. Do they know 'Body and Soul'? Do they know 'Don't Blame Me'? So we knew we were progressing, see?

Benny Golson

The Other Side (1958) signed by Benny, Curtis Fuller, Barry Harris

After that concert was over, we went backstage, like kids do, and got everybody's autograph. It was an evening concert and Charlie Parker was going over for the first show at a place called the Downbeat. And so, John (Coltrane) and I were walking up Broad Street with him, and John was saying, `Can I carry your horn for you, Mr. Parker?' I'm on the other side saying, `What kind of mouthpiece do you use? What kind of reeds do you use? What strength reed do you use? What is the make of your horn?' This crazy kid stuff, and he was telling it all and I thought I was getting the real lowdown. We got to the club, of course we were too young to go in, and he said, `Kids, keep up the good work,' and he went upstairs. We spent the night just standing out front listening to them play from up on the second floor, and walked home talking about it after it was over. This was exciting stuff to us, you have to believe that.

Benny Golson seeing Charlie Parker/Dizzy Gillespie with John Coltrane

The Modern Touch (1958) signed by Benny

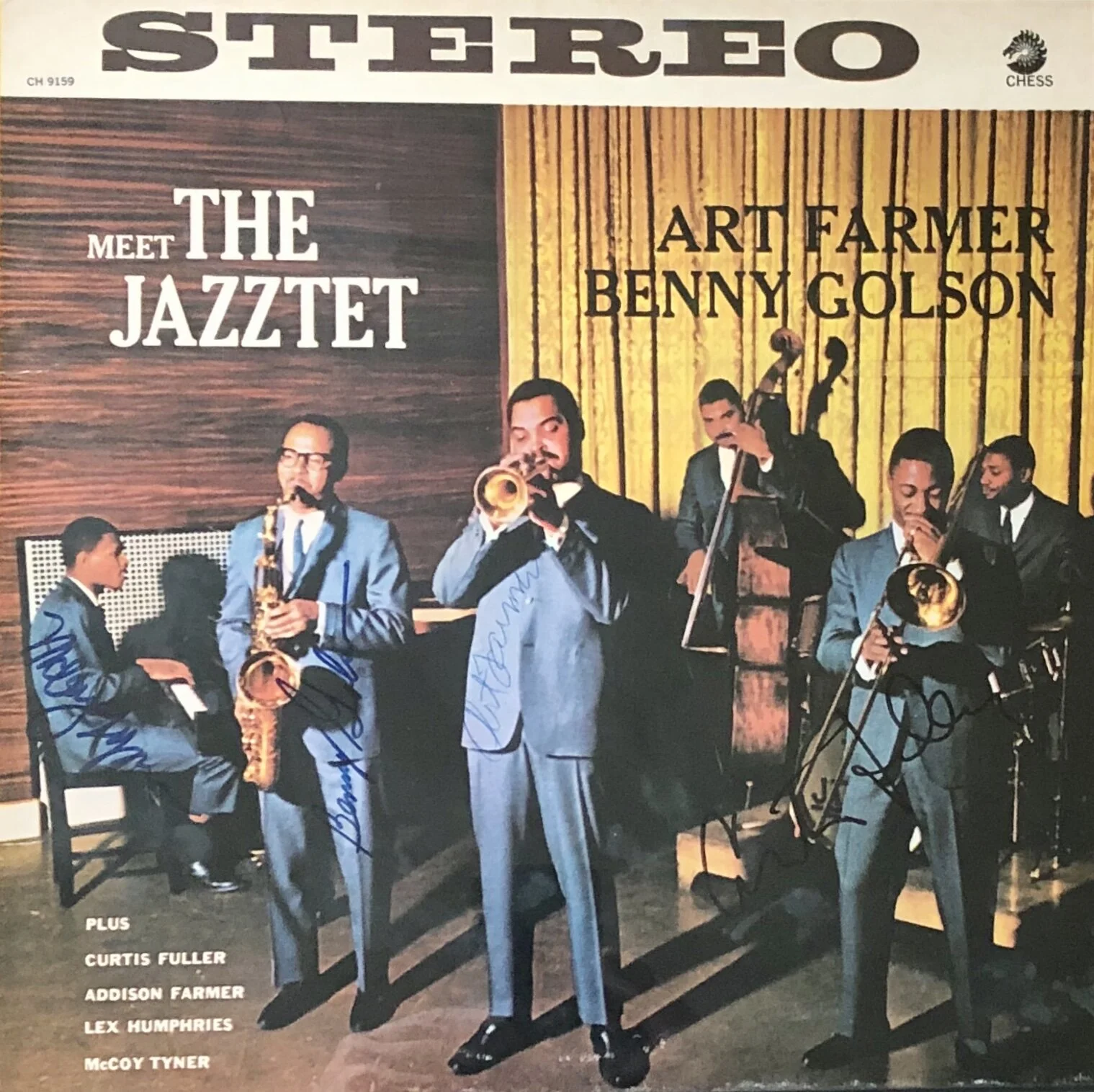

On his 1960 masterwork Meet The Jazztet, Benny Golson's "Killer Joe" introduces some of the first rap (well before Isaac Hayes, The Sugarhill Gang, etc.), as Benny describes "Killer Joe" as a fly dude in the spoken word intro:

"We'd like you to meet a friend of ours who goes by the name of Killer Joe. Picture a so called hippie or hip cat standing on a corner in a neatly pressed, double breasted form fitting pin striped suit, a pair of pointy toed shoes with bowl white stitches around the soles, a black shirt, a long white tie, a black pencil mustache and, of course, a very wide brim black felt hat. Killer Joe always has a pocket full of loot, but only the kind that jingles, you see, he likes to play the horses. He is most certainly a ladies man. As a matter of fact, he is always going to accept cash contributions from them for any cause, namely his own. The most important thing about Killer Joe that you have to know is that he's very much against manual labor. Killer Joe...."

A bluesy, soulful funk, "Killer Joe" has appeared on over sixty albums by artists as varied as Lionel Hampton, Quincy Jones, Jack McDuff, and Tito Puente. A gifted performer, Benny is a skilled and prolific composer of more than three hundred songs, among them, "Along Came Betty", "Blues March", "I Remember Clifford", "Stablemates", and "Whisper Not" - all well worn and recorded jazz standards.

Groovin’ With Golson (1959) signed by Benny, Ray Bryant, Curtis Fuller

Benny grew up in Philadelphia and some of his school mates and friends were John Coltrane, Jimmy Heath, Ray Bryant, and McCoy Tyner, most Philly born and bred, and (eventual) jazz legends. After three years of study at Howard University in Washington, DC, Benny left to join the Bull Moose Jackson Big Band, and then he enjoyed stints with Tadd Dameron, Lionel Hampton, Dizzy Gillespie, and Art Blakey where his real education as a musician began. As Benny observed, "After I left Howard, I drove a furniture truck. Jazz is so much better!" For three years, Benny co-led The Jazztet with Art Farmer and released six critically acclaimed albums. To date, Benny's discography has more than forty-five albums as a leader and he has appeared on hundreds more as a saxophonist, writer, and arranger.

The Curtis Fuller Jazztet (1959) signed by Benny, Curtis Fuller

Another Git Together (1962) signed by Benny, Art Farmer, Harold Mabern

In the early 1960s, Benny moved to Hollywood for a lost decade or more as he wrote scores for the television shows, Mission Impossible, M*A*S*H, Mod Squad, Ironside, and The Partridge Family. Yes, it is hard to believe that a musician as gifted as Benny Golson was writing Partridge Family scores while Shirley Jones, David Cassidy and Danny Bonaduce engaged in their mindless and soulless drivel on screen, but I am sure it helped to pay Benny's bills!

Al De Lory M * A * S* H (1970) signed by Benny

The Hollywood hiatus, however, did exact an artistic toll. As Benny later admitted, "For seven or eight years I didn't play my horn at all. I could have used it as an ornament or put dirt in it and planted flowers. I did not like my sound or my style, what I was playing wasn't reaching my heart, and I didn't know what to do about it. I was studying composition privately, I wanted to do some things I hadn't done before in composition. Once I moved, I put all my energy into that, and the playing fell aside. But the thinking process was working the whole time, and when I finally picked up the horn again in the late '70s, I sounded different, although it took about ten years before I felt comfortable again. I had to get my imagination oiled up."

Back To The City (1986) signed by Benny, Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller

After this sustained absence, Benny returned to the jazz scene with a vengeance. He regrouped The Jazztet with the formidable front line of Art Farmer on trumpet, Curtis Fuller on trombone, and Benny on tenor saxophone, and Erin and I saw them perform at Charlie's Georgetown in 1983/84. Charlie's Georgetown was an elegant supper club in Washington, DC named after local jazz guitar great Charlie Byrd who often performed there. Benny and The Jazztet performed a wonderful set which included "Along Came Betty", "Killer Joe", and "I Remember Clifford", a beautiful, elegiac ballad written as a tribute to Clifford Brown, a trumpet prodigy whose life was cut tragically short at age twenty-five in a car accident. It was an exquisite set, flawlessly executed.

Real Time (1986) signed by Benny, Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller

Many years later, I saw Benny perform several times at the Jazz Standard in New York City. Seeing him in concert was like going to a master class in Jazz. Benny is an expert story teller and craftsman with the mien, manner and erudition of a jazz scholar. Which he is. Benny would introduce each piece with an anecdote of where it was written, who performed it, and, as equally important, the song title. Too often, I have gone to jazz concerts where the artists assume that each member of the audience has attended Julliard or Berklee, performing a rigorous set with nary an explanation or song title offered. It is infuriating. More than once after a show, I have asked an artist in the dressing room which songs they had played. That never happens with Benny, and I always came away smarter for seeing him.

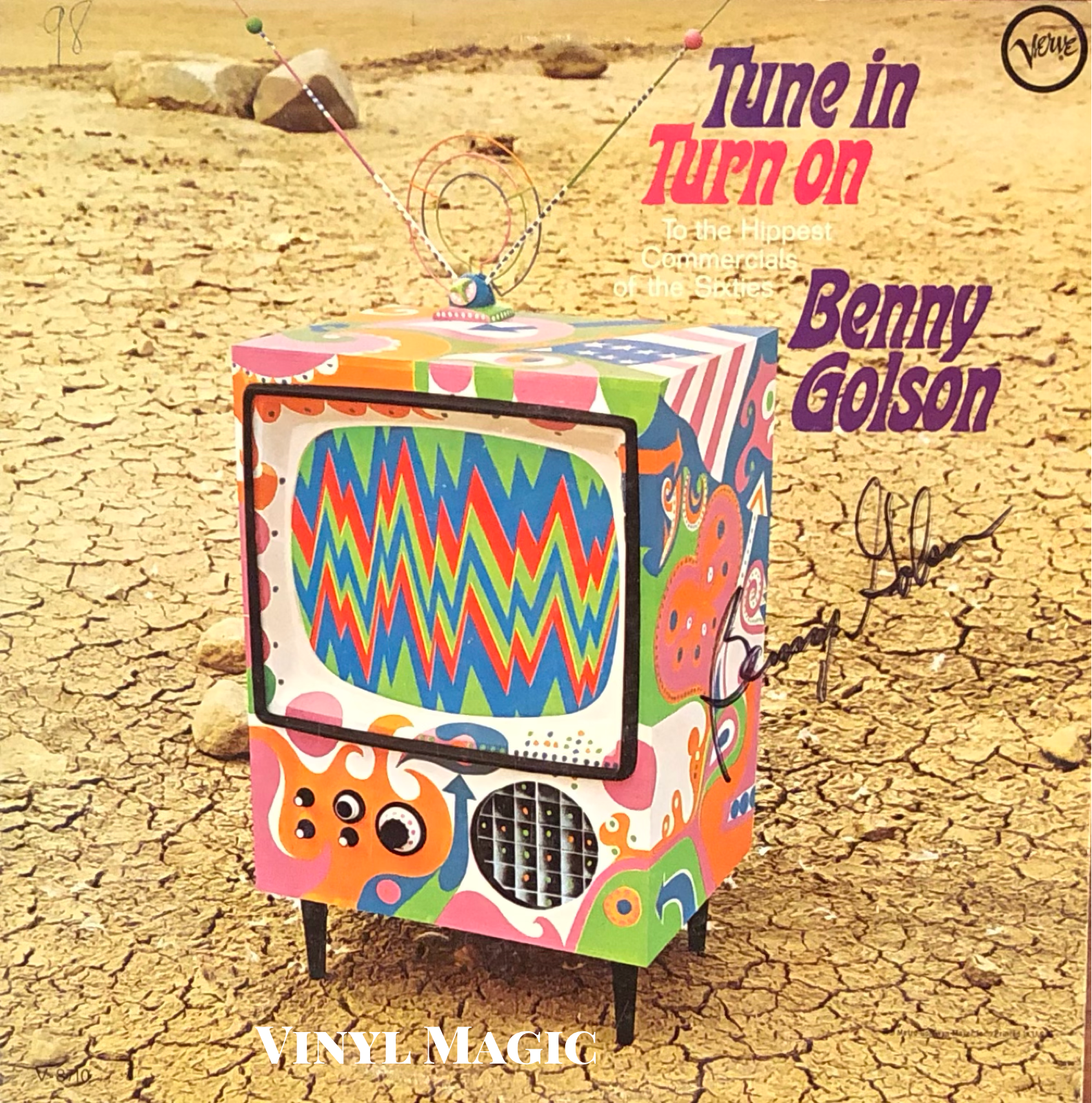

Tune In, Turn On (1967) signed by Benny

Benny was equally kind and generous off stage. He patiently looked through each album as he was signing. He loved Meet The Jazztet, one of McCoy Tyner's first album appearances and he appreciated the classic mid-century design of The Modern Touch (photographed in his apartment) and The Other Side, from the design team of Paul Bacon and Paul Weller. He laughed when he saw the cover of Tune In, Turn On, a song collection of "The Hippest Commercials Of The Sixties" with a phosphorescent, psychedelic television. A throw away collection of Madison Avenue "Mad Men" songs like "Cool Whip", "No Matter What Shape (You're Stomach's In)", and the (then omnipresent) Marlboro cigarette theme, "The Magnificent Seven", it is a colossal waste of the estimable jazz talents of Art Farmer, Eric Gale, Bernard Purdie, and Richard Tee. "Not my best recording", Benny duly admitted. He was especially kind when he signed the John Coltrane tribute album to my children: Kendall, Brendan and Camryn. Not the easiest names, and I have albums signed by other artists that are indecipherable, but he listened intently to each spelling, and carefully inscribed each name. He also gave me his business card and told me to call him some day and we could hang out and talk jazz. Unfortunately, I never made that call, not wanting to intrude on his privacy. For me, a rare show of restraint.

This Is For You John (1987) signed by Benny, Ron Carter

As Benny so eloquently stated in a recent interview, "Why continue to sound the way I sounded 30 years ago? That's not moving forward. Time should become your confederate. You should lock yourself in tandem with time on its one-way journey, moving ever forward. That's the way creative people should be moving - ever forward into the darkness of the unknown where things are awaiting your discovery. That's the adventure. You can play it safe. Everybody can do what you see in the light. But the real hero is the one that delves into the darkness."

Benny Golson, always moving forward as an artist, arranger, composer, and a really nice guy.

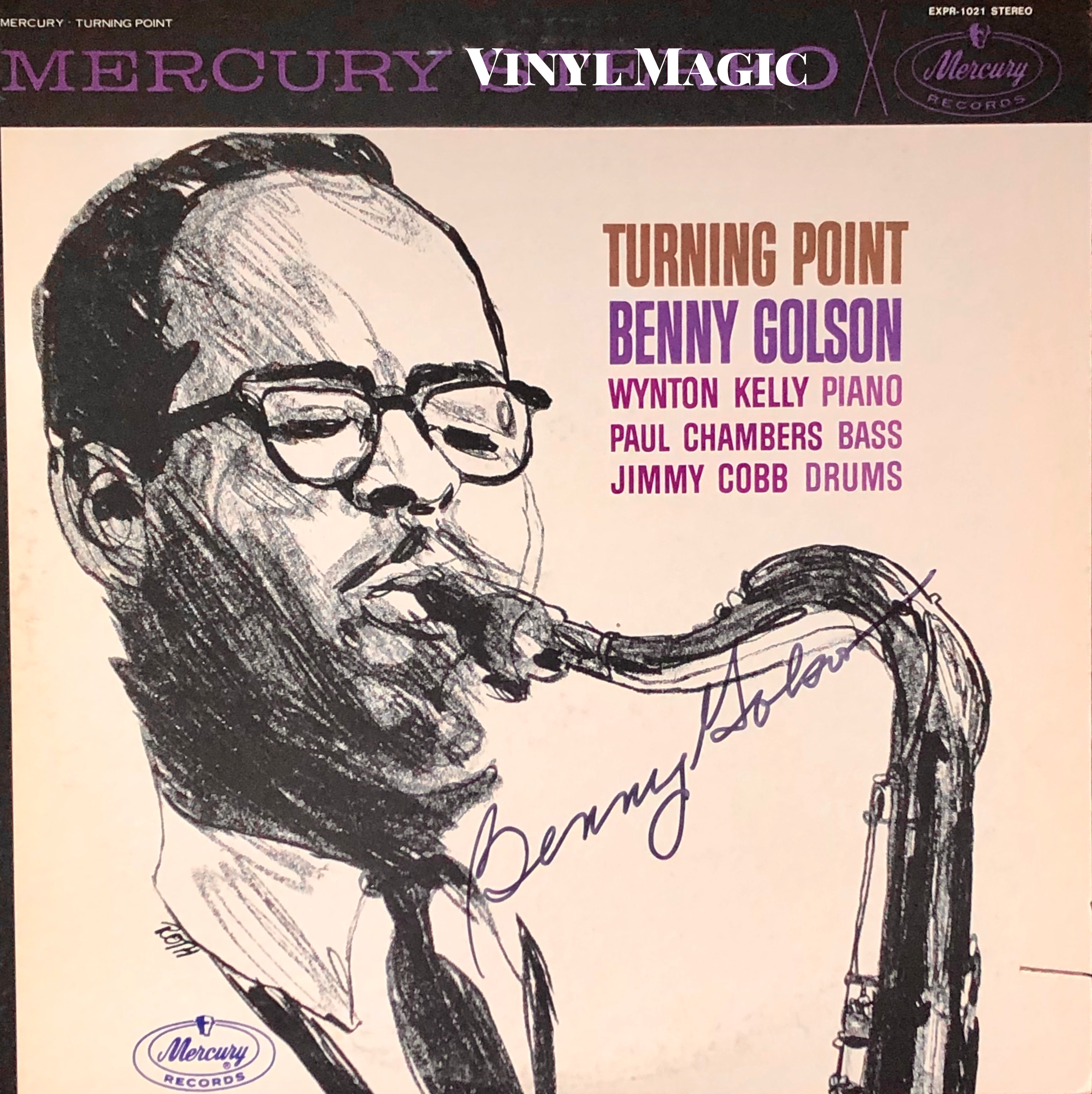

Turning Point (1962) signed by Benny

Blues ette (1959) signed by Benny

The Compositions Of Benny Golson (1962) signed by Benny

Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (1963) signed by Benny, George Coleman, Charles McPherson, Richard Wyands

Stockholm Sojourn (1964) signed by Benny

Choice Benny Golson Cuts (per BK's request)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WZQpxZ9cG-Y

"Killer Joe" - with intro - 1960

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nr7wcGmh12A

"I Remember Clifford" Live - 1958 - with Lee Morgan, Art Blakey

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bCXnH2JhpEk

"I Remember Clifford" Live with Milt Jackson

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVnVYa_x0AY

"Stablemates" Live - 1989 - with Freddie Hubbard

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVnVYa_x0AY

"Whisper Not" Live - 1987 - with Freddie Hubbard, Ron Carter

Benny Golson business card, circa 1999

Eight Jazz Classics (1979) signed by Benny